Is Tree Pruning Necessary Every Year?

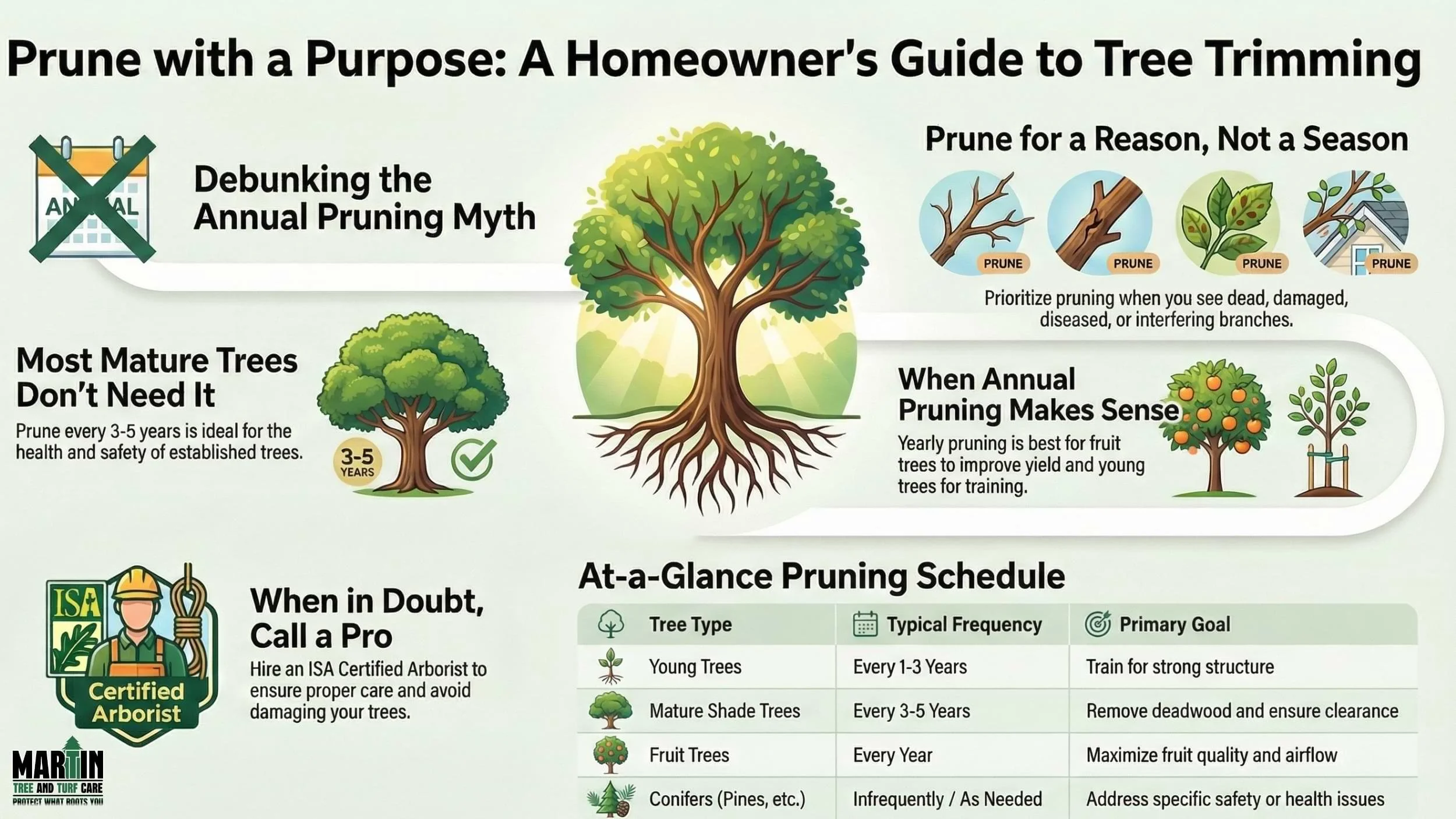

No. Most trees do not need pruning every year.

A practical baseline is every 3 to 5 years for mature shade trees, every 2 to 3 years for young-tree structural training, and annual pruning for many fruit trees. That baseline shifts when risk shifts. A limb over a roof, driveway, or service drop changes priority fast. Pruning works best as risk control, not a yearly tradition.

Pruning Frequency Guidelines

General Frequency for Mature Landscape Trees

Most established trees settle into a stable rhythm once structure is set. Work becomes periodic, not constant.

According to Clemson University Home and Garden Information Center, pruning needs vary by species and site. Poor timing or improper cuts can increase pest and disease pressure, which makes “every year” a weak default.

A common cadence for mature trees is every 3 to 5 years for deadwood removal, clearance, and canopy risk reduction. That interval allows normal recovery without forcing stress cycles.

General Frequency for Young Trees

Young trees follow different rules. Early decisions shape decades of strength and safety.

Clemson HGIC explains pruning is not needed in the first year after planting. Structural pruning typically begins in the second season and repeats every 2 to 3 years through about year ten to establish a central leader and well-spaced branches.

For example, correcting competing leaders is simple when branches stay small. Waiting often turns training into major reduction later.

When Yearly Pruning Makes Sense

Annual pruning fits when the purpose stays clear and consistent.

Fruit trees commonly receive yearly cuts to manage light, airflow, and crop load. Training and production goals require regular attention.

Tight sites also justify more frequent work. Rooflines, driveway clearance, and sightline control may call for smaller routine cuts instead of large corrections.

When Less is Better

More cutting does not equal better care.

Research-based guidance emphasizes removing defects and preserving foliage for photosynthesis and energy reserves. Heavy pruning often triggers dense, weak regrowth that increases future risk.

For mature trees with established structure, focus on defects rather than cosmetic thinning.

Key Deciding Factors

Start with targets and defects. Leave aesthetics for last.

Use a simple ground-level checklist grounded in arboriculture basics:

Dead, diseased, damaged, and deranged branches first. The “4 Ds” keep pruning tied to safety and health.

Targets set urgency. A limb over a bedroom carries more risk than one over a back fence.

Site constraints matter in Upstate yards. Roof edges, gutters, patios, vehicles, sidewalks, and service drops create real consequences.

Power lines are a hard stop. Work near energized conductors requires specialized planning and trained crews.

Pruning Timing

Timing follows biology and risk, not convenience.

Late winter to early spring works well for many trees because structure is visible before growth surges. That window supports clean decisions.

Flowering trees follow bloom cycles. Clemson notes many spring bloomers set buds early, so pruning at the wrong time reduces next season’s flowers.

Dead or dying limbs deserve faster action. South Carolina forestry guidance supports prompt removal to limit decay spread.

Storm response overrides season. Hangers and cracked unions present immediate hazards.

Pruning Techniques

Technique determines whether pruning reduces risk or creates it.

Professional work references ANSI A300 for cut quality and ANSI Z133 for safety in arboricultural operations. These standards exist because poor cuts and unsafe methods fail predictably.

Thinning and Reduction Cuts

Thinning cuts remove a branch back to the trunk or parent limb. This preserves natural form while improving clearance.

Clemson recommends starting with rubbing, crossing, dead, diseased, and dying branches, then thinning only as needed.

Reduction cuts shorten a limb to reduce end weight. This matters over roofs and drive lanes where leverage increases failure risk.

Cut Placement and the Branch Collar

Proper cuts protect the branch collar and branch bark ridge.

ANSI A300 specifies cuts outside the branch bark ridge and branch collar without tearing bark. USDA Forest Service guidance supports this biology-based approach for faster wound sealing.

Flush cuts and long stubs raise decay risk. Clemson explains stubs slow healing and invite insects and disease.

Large Limb Removal and Load Control

Large limbs demand load control and clean separation.

Clemson teaches the three-cut method to prevent bark stripping. Landing zones matter. When limbs cannot drop cleanly, rigging and controlled lowering protect siding, roofs, and fences.

Practices to Avoid

Topping is not pruning. It damages canopy structure and drives weak sprout growth.

Lion tailing also raises risk. Removing interior foliage shifts weight outward and increases wind leverage.

Specific Tree Types and Needs

Species biology changes outcomes. Growth rate, bud behavior, and wood strength shape response to cuts.

Young Structural Trees

Training delivers the highest lifetime value.

Clemson’s structural pruning schedule builds a strong central leader and branch spacing that reduces storm breakage later.

Mature Shade Trees

Routine annual cutting rarely helps.

Once structure is set, defect-based pruning and clearance usually cover safety needs. The “4 Ds” approach fits best.

Fruit Trees

Fruit trees are managed, not merely maintained.

Annual pruning balances fruiting wood, sunlight, and limb strength under crop load.

Conifers and Broadleaf Evergreens

Evergreens often need less routine pruning when planted to fit the space.

Clemson notes many conifers do not regenerate from old wood after severe cuts, which makes heavy pruning risky and often irreversible.

Pruning Safety and Professionals

Risk rises fast when targets exist.

Roofs, vehicles, patios, and people turn yard work into controlled removal. ANSI Z133 defines safety requirements because consequences escalate quickly.

Credentials help filter expertise. The International Society of Arboriculture states its Certified Arborist credential is accredited by ANAB under ISO 17024, supporting consistent knowledge standards.

Power-line proximity raises stakes. Utility-adjacent work requires strict controls, and errors can become catastrophic in seconds.

The Bottom Line When It Comes To Tree Pruning

Annual tree pruning is not the default.

A stronger approach pairs annual inspections with pruning on the schedule the tree actually needs. Clemson guidance supports structured training for young trees and purpose-driven work for established canopies.

I’m James Martin with Martin Tree and Turf Care. Our crews handle pruning, hazardous limb removal, and storm-risk work across Upstate South Carolina, including Greenville, Spartanburg, and Anderson. Call our office when you want a safety-first plan that protects your home, your yard, and the people who live there.